Thanksgiving week: turkey in a bubble, loved ones on Zoom and despite hope for the future, still having to turn the news off most of the time. And yet, there is so much to be grateful for. Of course, there are friends and family, a roof over our heads and all the doctors, nurses and delivery people who are doing their utmost to keep us afloat. But this year, I’m going to add something new to my list, something I’d taken for granted in the past: force of character, as defined by psychologist James Hillman as “appreciating ourselves as forces of nature.”

Speaking in terms of character at this moment of history seems like a stretch, given how much of this past year many of us have spent exploring the dark side of not only humanity but our own contributions. I’ve had to both process and attempt to rectify what I thought in many cases was a noble acceptance of differences, but that may in truth have run more along the lines of complacency. I’ve had abundant time to take the deepest dive yet into life review and in the shadow of political unrest, racial injustice and covid, feeling less like a force of nature than part of some grand experiment that has gone wildly wrong.

Which brings us to this January’s selection of the online Sage-ing Book Club, James Hillman’s The Force of Character and the Lasting Life. Hillman doesn’t begin to flinch when he peers into humanity’s shadow eye-to-eye. And what’s more, as a Jungian psychologist, he can see clearer than most in the dark.

In his compelling pages, I found multiple variations of all the ways, even with the best of intentions, we can go wrong. I located my own particular brand of incorrigibility somewhere on the spectrum between “muddled agitation” and “heightened irritability” with a healthy dose of possibly deluded bravado spicing things up. But Hillman does not judge any of this. In fact, he relishes all of our human foibles as the embodiment of archetypes necessary to be uniquely distinctive while simultaneously contributing to the whole. He writes: “Aging brings out all sorts of contradictions in human nature. All the complexes composing personality leap out of the basket. You become an unpredictable hydra—smiling, snapping, happy, grouchy, grumpy—all seven dwarfs.”

According to Hillman we can do what we can to cultivate more desirable habits, but we will never succeed at achieving the misguided and oversimplified ideal our culture thinks of as being of good character. Rather, we can cultivate an appreciation for force of character. “Some of what I mean by ‘force of character’ is the persistence of the incorrigible anomalies, those traits you can’t fix, can’t hide, and can’t accept…”, comprising a unique eccentricity that has less to do with striving for moral perfection and more to do with appreciating ourselves as forces of nature. “Character forces me to encounter each event in my peculiar style. It forces me to differ. I walk through life oddly. No one else walks as I do, and this is my courage, my dignity, my integrity, my morality, and my ruin.”

So what are we left with—in this romp towards ruin? In an understanding that disavows fixing, hiding and even acceptance, when you embrace your shadow, it does not magically transform into serenity. When you embrace your anger, you are still angry. Embrace your selfishness, you are still selfish.

But at the same time, we are not only our least desirable traits. When we tell the whole truth, the things we don’t like about ourselves are not all of who we are, and neither are the things we like least about the world all there is, either. There are, one assumes, things we like—even love—about ourselves and the world, as well. On the last page of Carl Jung’s autobiography—a culminating moment where one of the greats takes the opportunity to ponder the meaning of his life, he writes: “I am astonished, disappointed, pleased with myself. I am distressed, depressed, rapturous. I am all these things at once, and cannot add up the sum. I am incapable of determining ultimate worth or worthlessness; I have no judgment about myself and my life. There is nothing I am quite sure about…”

Jung is as rapturous as he is depressed. And, too, when it comes to me and to all of us—it’s, well, complicated. Educator Parker Palmer reminds us of the exchange between the nineteenth century transcendentalist Margaret Fuller and the writer Thomas Carlyle. “I accept the universe,” proclaimed Fuller. “Gad! She’d better,” replied Carlyle.

So here I am, as promised, with my own distinctive mix of delusion and bravado believing that I now have the solution to embracing one’s shadow—which, by the way, I can’t help but hope you will find inspiring.

If it weren’t enough to have compassion for one’s self nor enough to have compassion for when one doesn’t have compassion for one’s self, what if one were to resolve to have compassion for one’s self for when one doesn’t have compassion for one’s self for when one doesn’t have compassion for one’s self?

But as one of my wiser friends, hearing me out, suggested in response: “Egads! Wouldn’t it just be simpler to be bad for a change?” Or maybe instead, I could just try being if not bad, incorrigible. And so, this Thanksgiving, this, too, goes on my list of things to be grateful for.

________________________

The Sage-ing Book Club will be discussing James Hillman’s book The Force of Character and the Lasting Life in the comment section below as well as on Zoom, January 20 at 4 eastern. Spaces are limited and attendance is by love offering to Sage-ing International. To register, click HERE

For a free subscription to Older, Wiser, Fiercer, click HERE

_________________________

TO START OR JOIN THE DISCUSSION ON THIS BLOG AND BOOK: You are encouraged to share your thoughts with me and our community at the bottom of this blog as it is posted below at CarolOrsborn.com.

SBC is Sage-ing International‘s live online book club centering on reading and discussing both classics and new literature about subjects important to those of us choosing conscious eldering.

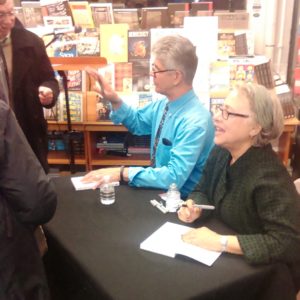

Co-leaders are Carol Orsborn and Jerome Kerner.